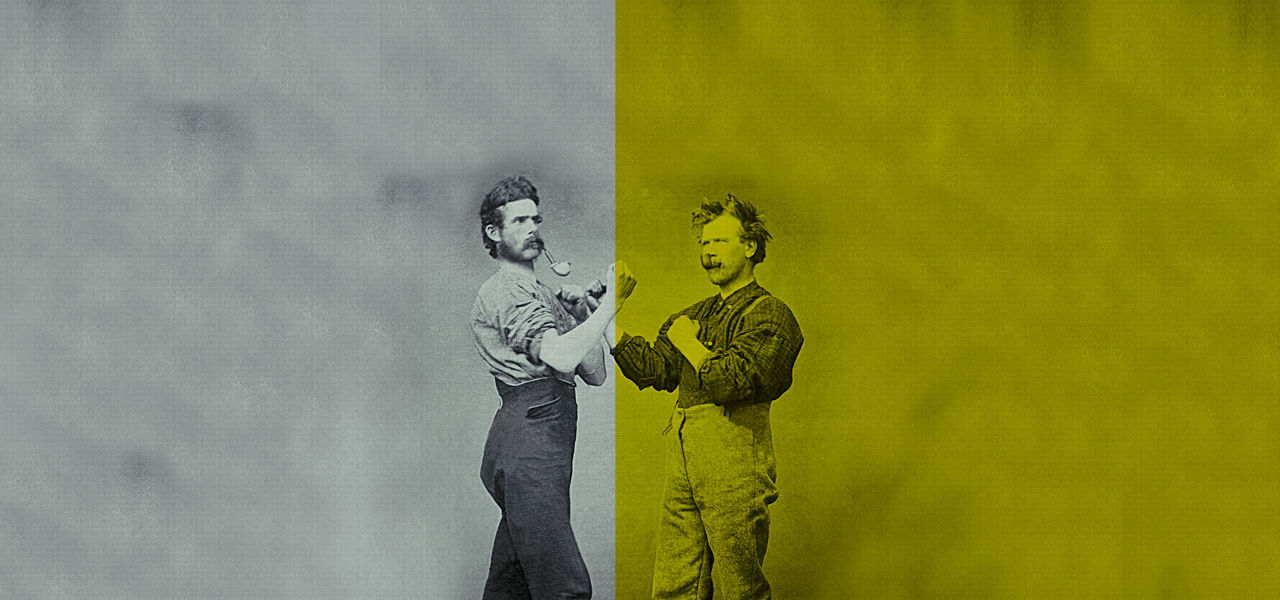

PUGILISUM AND CATCH WRESTLING

When did Victorian boxing and wrestling start? And who were the boxers and wrestlers?

Victorian boxers and wrestlers?

Pugilism in 19th-century London was not all fun and bad-taste animal antics. Exploring the lives of some of the most prolific and successful names in boxing and wrestling over the 1880s and 1890s – a key period of development for both sports – exposes countless stories of poverty and alcoholism, punctuated by lengthy prison sentences. There are murders, mysterious disappearances, and tragically early deaths.

Woolf Bendoff was a tough and dangerous man in the boxing ring and an even worse one out of it, serving prison terms for attempted murder, assault and handling stolen goods. John Devonport and James Haynes, alias ‘Jack Davenport’ and ‘Jem Haines’, two African-American heavyweights based in London, headlined large venues between doing time for drunkenly assaulting police officers, strangers or their female companions. Haines died at 30 from tuberculosis. Davenport cut hair, worked as a nightclub doorman, and was rumoured to have entered a mental hospital in his later years.

The respectable wrestler Walter ‘The Cross-Buttocker’ Armstrong was jailed with hard labour for cheque forgery in 1884, but by the end of the decade had published a book on wrestling and become a reporter for the Sporting Life. Tom Thompson broke both legs and was dead by 37, neither incident involving a donkey.

Hezekiah Moscow, a pugilist and bear tamer based in Whitechapel and also known as ‘Ching Hook’, had a successful boxing career in 1880–1891, toured the country as a comedy sketch artist in 1892, then disappeared on his wife and baby, never to be seen again. His friend Alexander Hayes Munroe, or ‘Alec Munro’, a mariner from Jamaica turned lion tamer turned boxer was stabbed in a boarding house in the East End in 1885, and died of infection in hospital.

The use of multiple nicknames and pseudonyms by prizefighters, many of them manual workers by day and professional boxers by night, combined with sporting newspapers’ inconsistent and racist reporting habits (often attributing white fighters to their home town or borough, but simply referring to black fighters as “black”, for example) makes a search for the men behind the ring personas a challenge. However, using old newspapers, census records, court transcripts and creative guesswork to trace individuals across careers in the ring and personal relationships builds an incredible insight into how brutal pugilism and life could be.

The story of boxing and wrestling in Britain dates back centuries, with rises and falls in popularity across decades, places, and on the backs of different people, the rare superstars proving capable of reinvigorating and reinventing their sport.

Victorian boxing and wrestling

British wrestling history is long and complex. Different regions developed different grappling styles, each with unique rules, traditions and flamboyant costumes, and when Irish, Scottish, Cumbrian, Cornish or Lancastrian men visited or settled in London, they brought their wrestling traditions with them. A hybrid style known as ‘catch-as-catch-can’ wrestling developed from the early 1870s but took a while to catch on, Jack Wannop of New Cross being among its chief proponents in the 1880s. Many wrestlers boxed too, and vice versa. From its roots in open fields and rural summer fairs, wrestling entered the pub back rooms and music halls of Victorian London, and by the early 1900s was an enormously popular entertainment, packing out theatres to audiences made up of thousands of our ancestors.

Wrestling is by its nature able to be performed in a collaboration between participants, as well as conducted competitively in an honest match. The origins of the choreographed or fixed theatrical entertainment that is so popular today lie in the exhibition matches or deliberately ‘thrown’ matches of the 19th century.

The golden age of English boxing started in around 1780 with Daniel Mendoza and Richard ‘The Gentleman Boxer’ Humphries, and was carried along by ToWith the introduction of an official police force in 1829 came the enforcement of laws outlawing prizefighting, and combined with a shift in attitude from the middle classes, fashionable interest had waned by the time Victoria ascended to the throne in 1837. Newspapers that had previously heralded boxing for being a masculine and heroic activity began to condemn it as morally wrong and physically dangerous. But boxing training and competition nevertheless remained immensely popular for men across social class and race.m Molineaux and Tom Cribb from 1810. It was both a working-class sport and a favourite of the aristocracy, and paradoxically considered quintessentially English yet dominated by immigrants.

I'm a With the introduction of an official police force in 1829 came the enforcement of laws outlawing prizefighting, and combined with a shift in attitude from the middle classes, fashionable interest had waned by the time Victoria ascended to the throne in 1837. Newspapers that had previously heralded boxing for being a masculine and heroic activity began to condemn it as morally wrong and physically dangerous. But boxing training and competition nevertheless remained immensely popular for men across social class and race.paragraph. Click here to add your own text and edit me. It's easy.

By the 1880s, seemingly every street corner in London had a gymnasium or ‘school of arms’, most commonly on the second floor or small back parlour of a pub, or in more substantial spaces in railway arches, members’ clubs and mission halls. In the late 1880s and early 1890s the Sporting Life as well as local and regional newspapers regularly reported on the opening of gymnasiums with the physical purpose of muscular development and boxing training, and a symbolic role in the ideas of ‘muscular Christian’ nationalism, discipline and self-pride. Boxing again meant all things to all people: both art and science, it was beloved by seasoned thugs and wholesome young boys alike.